This article is intended for medical and/or aged care professionals. For a consumer-oriented overview of IAD, see our blog article on the subject. All references used in this article can be found at the end.

What is Incontinence Associated Dermatitis?

IAD is one of many conditions under the umbrella of moisture-associated skin damage (MASD). The Clinical Excellence Commision of the NSW government defines it as "a type of irritant contact dermatitis (inflammation of the skin) found in people with faecal and/or urinary incontinence" (Connolly, 2021).

Is is also commonly known as "nappy rash", though refering to it as such is discouraged due to the disparaging & infantilising nature of the term. The risk of IAD developing increases with heavier levels of incontinence, this is due to the greater frequency and duration of exposure. Mixed faecal and urinary incontinence causes more damaging than either one alone.

A Refresher on Incontinence

To understand IAD, an understanding of incontinence itself is paramount. Incontinence is the "accidental loss of urine (wee) from the bladder [and/or] faeces (poo) or flatus (wind) from the bowel (Continence Foundation of Australia, 2023).

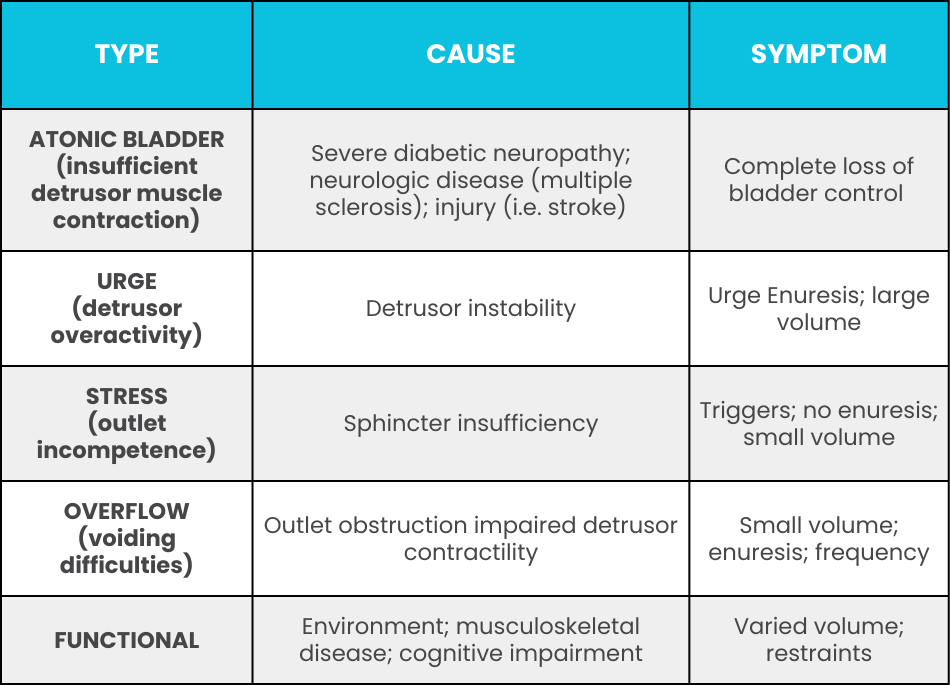

The condition can appear in many variations. It can be exclusively urinary or faecal or occur mixed, while also having many types (Tran & Puckett, 2024):

- Stress (increased intraabdominal pressure leaks to leaks due to pelvic floor weakness)

- Urge (aka overactive bladder; bladder emptying involuntarily with little warning e.g. as a result of nerve damage)

- Overflow (bladder filling beyond its capacity and voiding without warning)

- Mixed (stress & urge incontinence occuring together), functional (external barriers such as poor mobility or dexterity inhibiting prompt & normal toilet use)

- Transient (temporary incontinence due to external, reversible causes like infections or stool impaction).

Likewise, incontinence can be caused in many ways. The table on the right shows possible causes for some types of urinary incontinence.

Similar to these many types & causes, incontinence can also have many effects and lead to other health concerns down the line. Aside from IAD, this can be a range of concerns such as mental health (depression potentially stemming from the loss of control over one's own body)(Broome, 2003) or social activity (embarrassment and isolation resulting from public incidents of incontinence & the stigma on the condition)(Pizzol et al., 2021).

Human Skin & the Effects of Incontinence on It

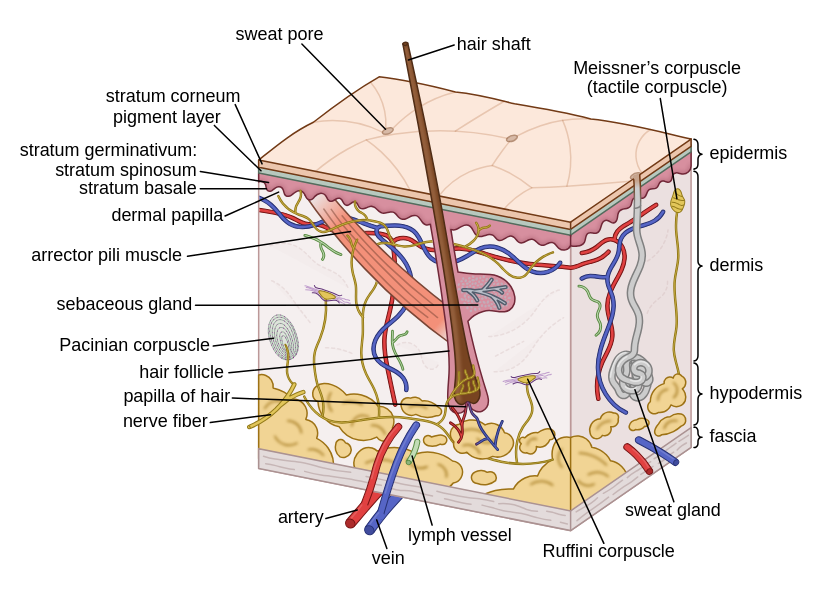

The skin is the largest organ in the human body, accounting for around 15% of the average human's weight. It consists of multiple layers:

The outermost layer, the epidermis, is further subdivided. Its outer layer is known as the stratum corneum, and consists of flat cells arranged in a brick-and-mortar pattern. This layer is made up of corneocytes, which are the final form of keratinocytes as they mature and develop (Murphrey et al., 2022). Beneath the corneocytes, keratinocytes migrate, proliferate, and differentiate to restore the epidermal barrier. This flexible barrier aids in hydration and water retention, protects from UV-exposure and microbial invasion (Chan, 2023).

Below that lies the dermis, which is made from collagen, supports & protects the deeper layers, and aids in thermoregulation & sensation (Brown & Krishnamurthy, 2022). Lastly, the hypodermis (also known as subcutaneous tissue), contains fat cells & sweat glands (Cleveland Clinic, 2021).

Generally, skin is acidic in nature, with the pH-level ranging from 4-6.

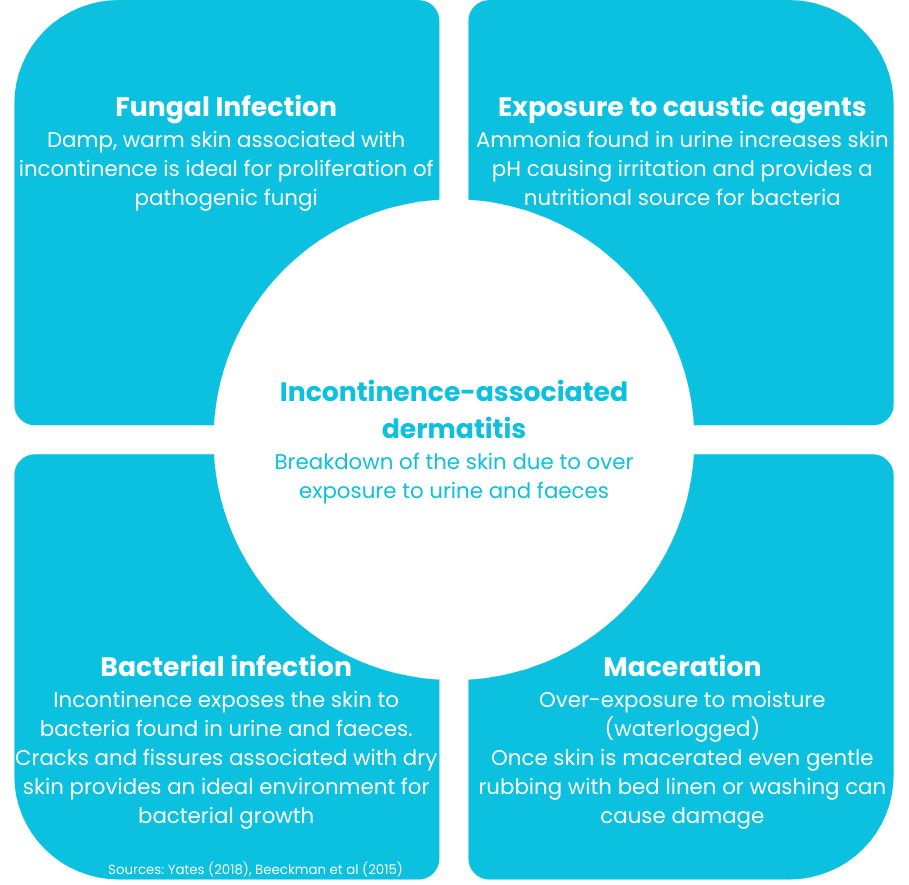

The contact with urine and faeces can change this, as when skin bacteria come in contact with urine they convert urea (a product of protein metabolism) into ammonia, which is alkaline. This raises the skin pH level, which in turn disrupts the acid barrier functionality. The skin becoming alkaline activates digestive enzymes, growth of bacteria, and fungi.

This then results in inflammation & ultimately denudation of the skin (Connolly, 2021).

These concerns are doubly prevalent in older people, mainly because of their hightened risk of skin damage. There are many reasons for this:

- Reduced skin elasticity

- Decreased collagen synthesis

- General atrophy of connective tissue

- Disrupted enzyme balance

- Reduced resistance, increased risk of friction damage

- Vulnerable to splitting/cracking due to quicker moisture/loss

- Slowed rate of healing

As the graphic on the opposite side shows, there are a number of impacts incontinence can have on skin and its integrity (Yates, 2108; Beeckman et al., 2015). The first and foremost among them is incontinence-associated dermatitis, or IAD.

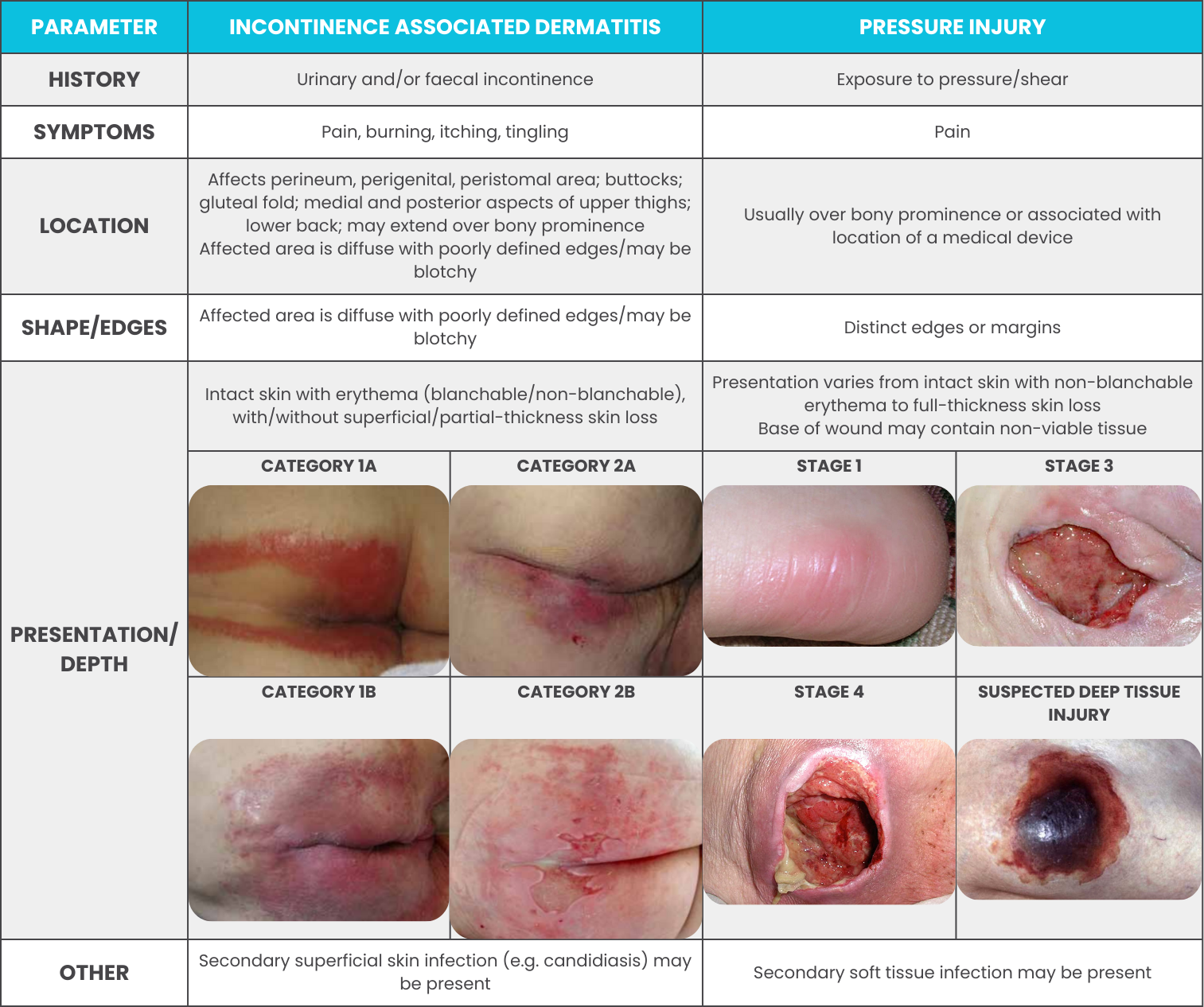

Incontinence-Associated Dermatitis vs Pressure Injury

A pressure injury (PI) is a localised injury to skin and/or undelying tissue usually over a bony prominence resulting from pressure by itself or in combination with shear and/or friction (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2018). Due to the characteristics exhibited by both conditions, it can be easy to mistake one for the other. That being said, their differences can be spotted if one knows what to look for. Consult the following table to see how IAD & pressure injuries differ.

Assessing & Categorising IAD

Every incontinent resident is to some degree at risk of developing IAD & requires a skin care regimen (Ticchi, 2018). This means that checking for IAD (or elevated risk thereof) has to be a regular part of a resident's continence assessment. The assessment of the skin for IAD involves the physical inspection of all possibly affected areas: the perineum, perigenital area, buttocks, gluteal fold, thighs, lower back, lower abdomen, and skin folds for the presence of any of the following:

- Maceration (softening and break down due to prolonged exposure to moisture)

- Erythema (redness of the skin)

- Presence of lesions (vesicles, papules, pustules, etc.)

- Erosion (a break down of the outer layers of skin)

- Denudation (a loss of the surface layers of skin)

- Signs of bacterial/fungal skin infection.

All findings & appropriate actions need to be documented in the resident's healthcare records. This ensures that all staff is up to date on the resident's condition & that action is taken where necessary. Additionally, this enables the assessment at regular intervals to chart the status over the entirety of the resident's stay, as well as the success of actions taken to combat IAD.

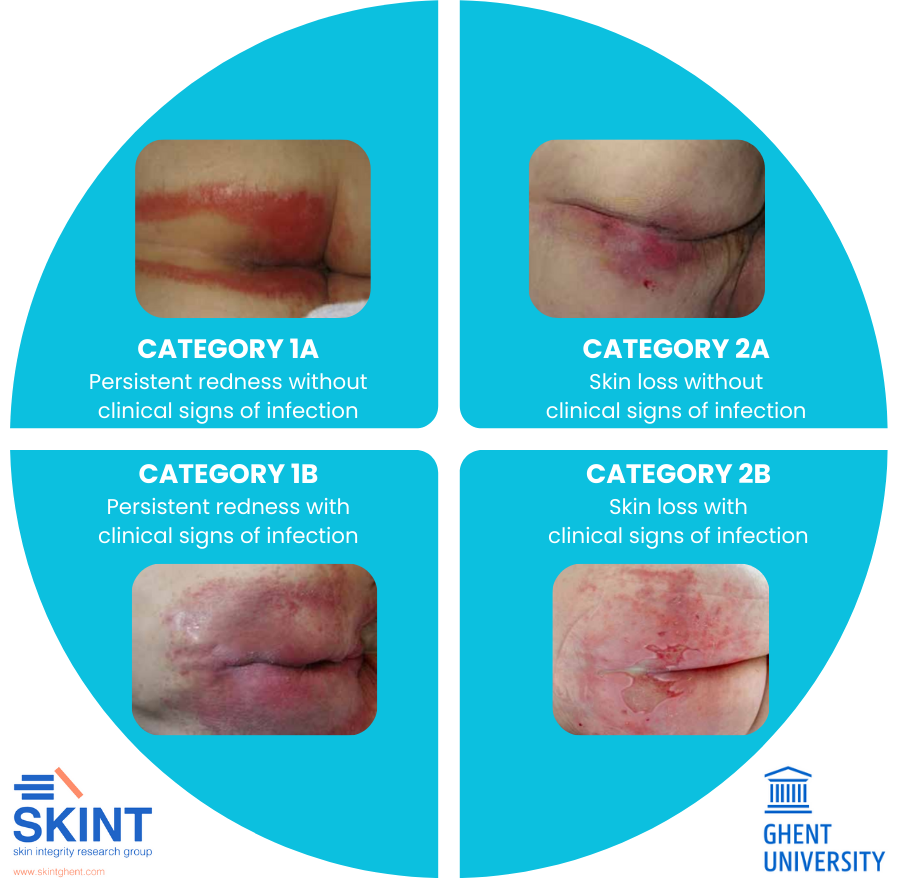

If IAD is present, it needs to be categorised to enable the targeted application of appropriate actions. Category 1 encompasses persistent redness of the skin, while category 2 encompasses skin loss. Additionally, each of these categories can exist without or with clinical signs of infection (denoted by the suffix letter A or B, respectively). This then creates four distinct possible presentations for IAD (Beeckman et al., 2017):

CATEGORY 1A

Critical criterion: persistent redness

A variety of tones of redness may be present. Patients with darker skin tones, the skin may appear paler or darker than normal, or purple in colour.

Additional criteria

- Marked areas or discolouration from a previous (healed) skin defect)

- Shiny appearance of the skin

- Macerated skin

- Intact vesicles and/or bullae

- Skin may feel tense or swollen at palpation

- Burning, tingling, itching or pain

CATEGORY 2A

Critical criterion: skin loss

Skin loss may present as skin erosion (may result from damaged/eroded vesicles or bullae), denudation or excoriation. The skin pattern may be diffuse.

Additional criteria

- Persistent redness

- A variety of tones of redness may be present. Patients with darker skin tones, the skin may appear paler or darker than normal, or purple in colour.

- Marked areas or discolouration from a previous (healed) skin defect)

- Shiny appearance of the skin

- Macerated skin

- Intact vesicles and/or bullae

- Skin may feel tense or swollen at palpation

- Burning, tingling, itching or pain

CATEGORY 1B

Critical criteria: persistent redness, signs of infection

A variety of tones of redness may be present. Patients with darker skin tones, the skin may appear paler or darker than normal, or purple in colour.

Signs such as white scaling of the skin (suggesting a fungal infection) or satellite lesions (pustules surrounding the lesion, suggesting a Candida albicans fungal infection).

Additional criteria

- Marked areas or discolouration from a previous (healed) skin defect)

- Shiny appearance of the skin

- Macerated skin

- Intact vesicles and/or bullae

- Skin may feel tense or swollen at palpation

- Burning, tingling, itching or pain

CATEGORY 2B

Critical criteria: skin loss, signs of infection

Skin loss may present as skin erosion (may result from damaged/eroded vesicles or bullae), denudation or excoriation. The skin pattern may be diffuse.

Signs such as white scaling of the skin (suggesting a fungal infection) or satellite lesions (pustules surrounding the lesion, suggesting a Candida albicans fungal infection), slough visible in the wound bed (yellow/brown/greyish), green appearance within the wound bed (suggesting a bacterial infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa), excessive exudate levels, purulent exudate (pus) or a shina appearance of the wound bed.

Additional criteria

- Persistent redness

- A variety of tones of redness may be present. Patients with darker skin tones, the skin may appear paler or darker than normal, or purple in colour.

- Marked areas or discolouration from a previous (healed) skin defect)

- Shiny appearance of the skin

- Macerated skin

- Intact vesicles and/or bullae

- Skin may feel tense or swollen at palpation

- Burning, tingling, itching or pain

Preventing IAD

Obviously, it is in resident's best interest to prevent IAD from ever occuring. But how can that be done?

As said in the previous paragraphs, every incontinent resident is at risk of IAD. Such risk should be regualrly assessed (e.g., as part of assessing their continence level or skin care regimen). Additionally, the risk is higher for residents suffering from diminished cognitive awareness, raised body temperature, or poor nutritional status. Furthermore, certain medications (such as immunesuppresants) can affect the likelyhood of IAD, as can the use of occlusive containment products or conditions that result in inability to perform personal hygiene, such as pain, critical illness, or compromised mobility (Connolly, 2021).

If the assessment shows a risk of IAD developing (but no existing IAD yet), there are a number of preventative measures that can be taken (Connolly, 2021).

- Use pH-balanced skin cleaning products instead of alkaline soaps,

- Pat skin dry or air dry instead of rubbing,

- Treat reversible causes & manage incontinence (prompt toileting & change of continence aids),

- Moisturise skin to prevent cracks,

- Use protective products (e.g., barrier creams),

- Ensure correct size/fit/absorbency of allocated continence aids.

The last point is especially important, as the continence aids are generally an incontinent resident's first point of contact between skin & irritant. This means that the right choice of continence aid can be the difference between IAD merely being a risk to watch out for or a condition developing. Additionally, if a resident was identified as being especially at risk of IAD developing, the interval of their skin assessment should be shortened to survey the success of measures taken & ensure IAD does not develop.

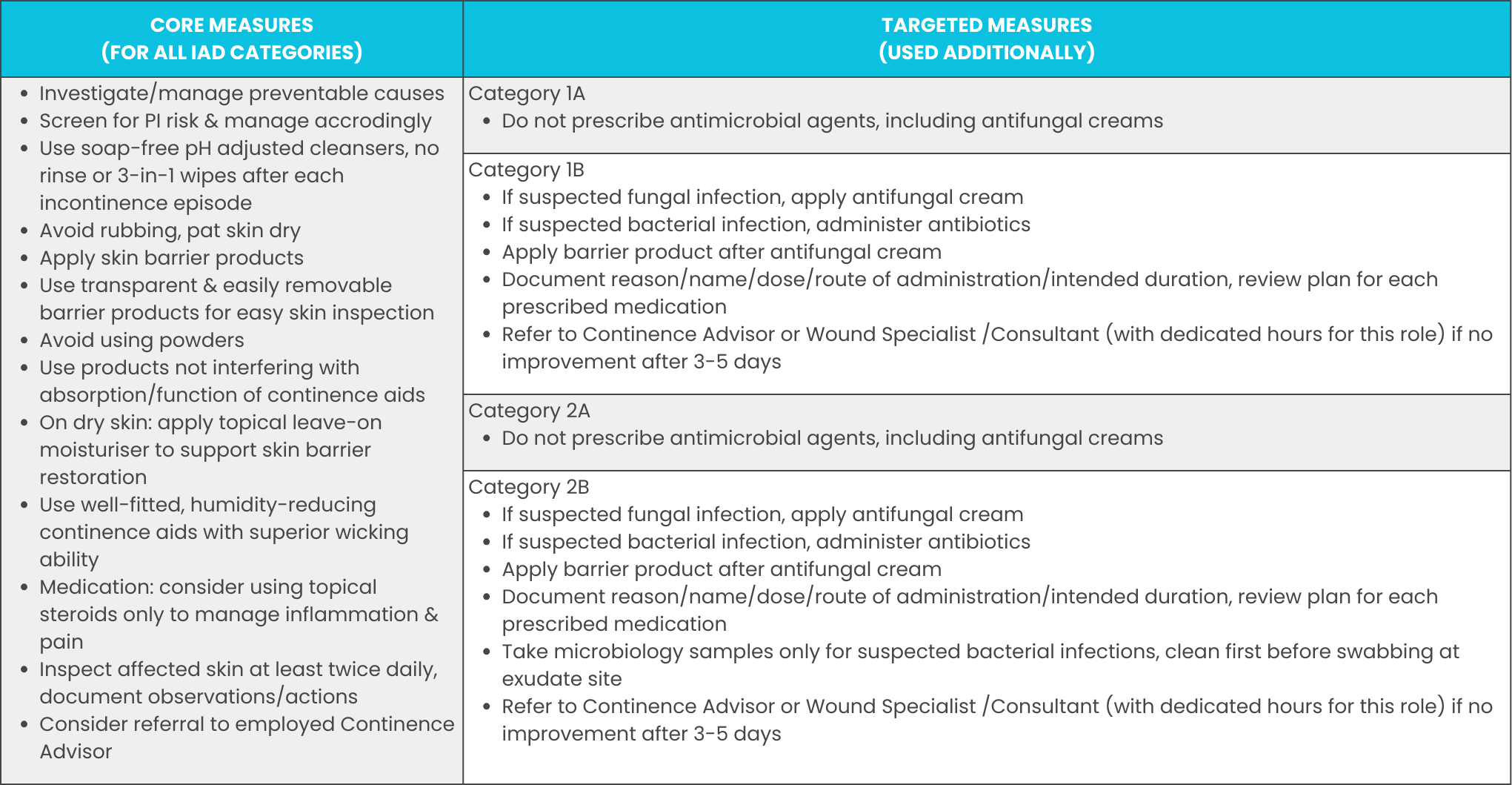

Managing IAD

If IAD has developed, it is generally discovered either by the residents themselves (due to the discomfort it causes) or by a carer (either during their duties or as part of a continence or skincare assessment). However, IAD is not just a condition that itself requires treatment, but also an indicator for another problem, namely that the current continence and/or skin care regimen is insufficient in one or more of the following ways:

Cleaning: If the resident is not cleaned properly and sufficient after episodes of incontinence, IAD can develop. Examples include incomplete cleaning leaving irritants on the skin, cleaning through rough rubbing agitating the skin or the use of standard (alkaline) soaps instead of pH-balanced products, contributing to skin irritation with frequent cleaning.

Skin Care: The use of wrong skincare products or no products despite necessity can lead to the development of IAD. For example: Failure to use moisturiser leading to cracked skin suceptible to IAD, or the use of products incompatible with continence aids blocking the aids and preventing absorbtion of urine.

Continence Aids: The use of continence aids of wrong size or insufficent absorbency, or the incorrect fitting to the residents can lead to IAD. Adequate continence aids are made from skin-friendly and breathable materials and remove moisture from the skin quickly to minimise contact between irritants and skin.

Toileting: Lastly, failure to toilet residents on a toileting schedule can lead to their exposure to irritants, where prompt toileting could have prevented some episodes of incontinence entirely, thus preventing contact between skin and irritants in the first place.

Improving the care provided in in these categories where necessary not only helps managing the current IAD issue at hand, it also helps ensuring a standard of care that helps preventing IAD in the future. This improvement & treatment generally encompasses the following general & specific treatments (Ticchi, 2018):

A Mnemonic for Continence Skin Care:

The Valui CARE-device

Based on the previous research & best practices, we have compiled a 4-step mnemonic for successful continence skin care:

Cleanse - Keep the skin free clean & free from irritants through the use of correct (pH-balanced) cleansing products, utilised in a way non-agitating to the skin.

Armour - Protect the skin of at-risk residents from IAD through preventative & protective measures such as barrier creams.

Restore - Restore continence wherever possible and utilise products like moisturisers to restore the skin's own barrier function.

Evaluate - Regularly assess the condition of residents' skin & continence to react to changes in time.

Thank you for taking the time to read this article. We hope that this exploration of incontinence associated dermatitis & its prevention and management has been useful to you. If you have any comments or suggestions for future topics, you can reach us through our contact form.

References

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2018). Pressure Injury.

Beeckman, D., Campbell, J., Campbell, K., Chimentão, D., Coyer, F., Domansky, R., . . . Wang, L. (2015). Proceedings of the Global IAD Expert Panel. Incontinence-associated Dermatitis: Moving Prevention Forward.

Beeckman, D., Van den Bussche, K., Alves, P., Beele, H., Ciprandi, G., Coyer, F., . . . Kottner, J. (2017) The Ghent Global IAD Categorisation Tool (GLOBIAD).

Broome, B. (2003). The impact of urinary incontinence on self-efficacy and quality of life.

Brown, T., & Krishnamurthy, K. (2022). Histology, Dermis.

Chan, L. (2023). Keratinocytes. In L. Chan, & V. Shi, Atopic Dermatitis: Inside Out Or Outside In.

Cleveland Clinic. (2021). Hypodermis (Subcutaneous Tissue).

Connolly, M. (2021). Incontinence Associated Dermatitis (IAD) Best Practice Principles.

Continence Foundation of Australia. (2023). Understanding incontinence.

Murphrey, M. B., Miao, J. H., & Zito, P. M. (2022). Histology, Stratum corneum.

Pizzol, D., Demurtas, J., Celotto, S., Maggi, S., Smith, L., Angiolelli, G., . . . Veronese, N. (2021). Urinary incontinence and quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Ticchi, M. (2018). Incontinence Associated Dermatitis with Suspected Infection A Guideline for Assessment and Management.

Tran, L., & Puckett, Y. (2023). Urinary Incontinence.

Yates, A. (2018). Preventing skin damage and incontinence-associated dermatitis in older people.